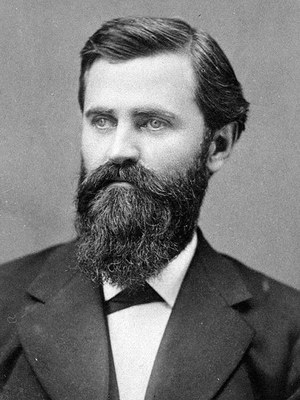

1871 - 1898 George Sumner Albee

In 1871, the Board of Regents selected George Sumner Albee to be the first President of the Oshkosh Normal School. Born in 1837 in Allegheny County, New York, Albee began teaching in 1855 at the age of eighteen. He later attended the Genesee Seminary in Lima, New York, and then the University of Michigan matriculating in the classical course and graduated in 1864. After teaching mathematics and natural science at Rushford Academy in western New York for two years, he became a principal at a public school in Peoria, Illinois until 1868. Similar positions followed in Kenosha, then Racine, Wisconsin.

Albee’s career in these various positions as well as his active involvement in professional organizations solidified his reputation as an educator. He became a member of the Executive Committee of the Wisconsin Teachers' Association in 1865 and served as its president from 1882-1883 and was the first president of the Wisconsin Principals’ Association. Albee’s early years in Wisconsin shaped his educational values having learned much from John McMynn, a leader of the Normal School movement and a highly respected educator in the state. Albee’s insight regarding the state and national goals of education informed his presidency of the Oshkosh Normal School.

Throughout his presidency, Albee was devoted to the development of high academic and professional standards. He believed the state’s public schools were of poor quality because students and communities relied on unprepared teachers. To him the Oshkosh Normal School provided opportunity to change the status quo. He stood by the motto: “Intelligence for the many, not the few,” a progressive, egalitarian philosophy that served him well in Oshkosh. During Albee’s twenty-seven-year administration, the Oshkosh Normal School became the largest Normal School in Wisconsin and a leading teacher training institution in the Midwest.

In the first month, Albee instituted an entrance exam requirement, administering it himself along with a personal interview with the applicant. Due to the variance in academic backgrounds, he organized preparatory courses (often for those rural students who had no local high school) to help prospective students pass the exams.

To ensure that students received a well-rounded education that prepared them for teaching careers, Albee proposed a curriculum that included the fine arts, physical education, natural sciences as well as rigorous teaching methods. Unfortunately, due to a limited budget, the Board of Regents felt that only core subjects were necessary in the training of teachers and would not grant funds for Albee’s desired programs. Undeterred, Albee raised funds on campus to hire teachers and purchase equipment for art, music, gymnastics and a science lab. These enhancements of the school’s curriculum without aid from the Board of Regents, was a testament to Albee’s commitment to the state and its children.

Albee was directly involved in nearly every aspect of the school’s administration and took a keen interest in the students. His strong religious convictions helped him maintain social morays on campus. Each morning he delivered sermons on various themes relating to ethics, disposition and the teaching profession. Albee’s religious practices drew criticism. Parents complained that the morning devotions deprived their children of school time and that they were an infringement on the rights of the students in a state institution. The morning sermons ended immediately after March 18, 1890, when in the State ex rel. Weiss v. District Board 76 Wis. 177 (1890), more commonly known as the Edgerton Bible Case, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled religious practices in Wisconsin public schools unconstitutional. Even though the rule brought change to campus, Albee and the school continued to train teachers with the social attitudes and morality of Victorian America.

Albee's relationship with his faculty was strained at times. The Office of the President held broad powers and there was no shared governance. His autocratic and paternalistic styles caused some professors to chaff, and at times rebel. In one case the faculty overruled Albee’s choices for commencement speakers, choosing their own instead. Still from many perspectives, Albee provided both educational and virtuous leadership which made him the very image of the school until his death on September 4, 1898.

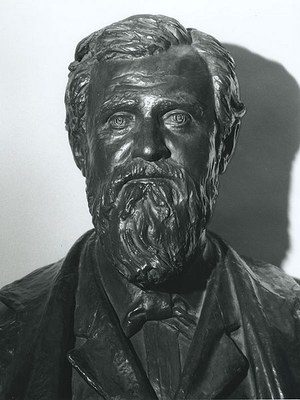

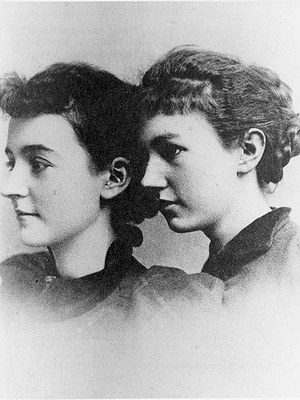

After his death, Albee’s colleagues formed a committee to establish a memorial celebrating his contributions to the development of the Oshkosh Normal School. The committee considered several options, including a beautification project and a scholarship. In 1899 the committee decided to commission Helen Farnsworth Mears, an internationally known Oshkosh-born sculptress and Normal School alumna, to create a marble bust of Albee based on his death mask. Paid $700 for her efforts, she modeled the bust in clay from which a plaster cast was made in Chicago and sent to a sculptor in New York, who chiseled the marble. The bust was unveiled on the first anniversary of Albee’s death in the auditorium of the Oshkosh Normal School. Unfortunately, the bust was destroyed in the Normal School fire on March 22, 1916 and only the right eye was found among the ruins. A new committee containing several members of the original memorial committee was formed, and commissioned a bronze replica of the marble bust, cast by Gorham Foundry in New York. It was dedicated on June 9, 1919 in the Normal School Library and currently resides in the University’s Archive & Area Research Center in Polk Library.

Photos

President George Sumner Albee

The bronze replica of Albee's bust

Scupltress Helen Farnsworth Mears, on left, and her sister.