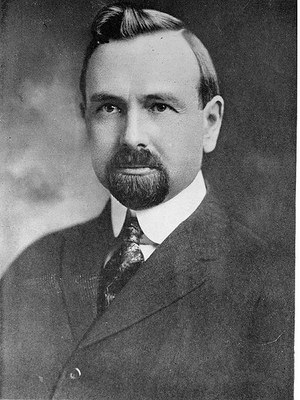

1917 - 1930 Harry A. Brown

The Oshkosh Normal School’s forth President was Harry Alva Brown who came to Oshkosh from his position as the Deputy Superintendent of Public Instruction of New Hampshire in 1917. He held degrees from Bates College (1903) and the University of Colorado (1907). Brown entered his presidency amidst World War I. America’s participation in the war, amplified the Normal School’s patriotism. Lecturers, like Jessie Jack Hooper, an Oshkosh suffragette, spoke to students about national and international events. Christmas packages were sent to students serving in the Armed Forces, and two Red Cross drives won the support of the school. During the years of the war, Brown also changed the curriculum. In February, 1918, he announced the start of two war lectures available to the senior class. That September, the Normal School became host to a Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.). The program allowed college and normal school students over the age of 18 to learn “the art of war’” while continuing their studies. Several campus buildings accommodated the program. The gymnasium served as the unit’s headquarters, and a building hastily made to temporarily house the Primary and Intermediate Departments after the fire of 1916, became the units living quarters known as the barracks. The unit proved short-lived, after Armistice, S.A.T.C. received its discharge on December 27, 1918.

After World War I, Brown focused on his academic mission. He believed in the leadership goals of the Normal School, and thus sought out to restructure the programs with new courses and methods. He introduced two and three credit courses and extended the concept of “major” and “minor” areas of study into the senior and junior high school curricula. Brown also did away the numerical grading system, and introduced a lettered system in the fall of 1924. Under the lettered scale, students who did not perform at a Satisfactory or B- level, could be put on probation or required to withdraw from the school.

During Brown’s administration, the Regents moved towards establishing a four -year teacher education curriculum. For years, the Wisconsin State Normal Schools petitioned the Board of Regents and state legislature to permit the awarding of undergraduate degrees (previously the schools only offered diplomas). The action, they argued, would allow fairer competition among Normal and University graduates in the job market. Opposition was fierce, the administrators of the University of Wisconsin and private colleges felt that the quality of Normal School education was not equal with their programs and should not result in the same degree. In February, 1925, a new bill went before Wisconsin’s Senate. The bill’s sponsor was Walter H. Hunt, a former professor at the River Falls State Normal School. Brown represented the Board of Regents at the bill’s hearings. The Oshkosh President pointed out that thirty-four other states granted degrees to their normal school graduates. In Brown’s opinion, Wisconsin’s public education system was not reaping all the benefits of its teacher education programs. Wisconsin school officials sought degree holding candidates, which made Wisconsin State Normal School graduates compete against out-of-state degree holders. After the legislature passed the bill, the Board authorized six degree related fields in which Oshkosh students could concentrate: rural education, elementary education, junior high school education, secondary education, industrial education and education for exceptional children, a precursor for Special Education. The campus applauded Brown and his efforts in relation to the bill are seen as the highlight of his presidency.

Soon after the new graduation requirements, the Oshkosh State Teachers College won distinctions for its high standards. In February, 1928, the American Association of Teachers Colleges awarded it “Class A” accreditation. That March, the North Central Association admitted the college to its list of teacher training schools. Also in 1928, the Rose C. Swart Training School opened, offering a sense of individuality that separated Oshkosh from other Teachers Colleges.

In an effort to achieve a high level of professionalism among the school’s faculty, Brown urged as many Oshkosh professors as possible to complete graduate work in education, and he arranged to have some of these graduate credits completed at Oshkosh. In 1930, Brown resigned to take the position as president of the Illinois Normal School. Shortly after his resignation, the credits he awarded to the Oshkosh faculty were called into question because there was no documented coursework to back them up. Brown defended the credits, but several accrediting bodies, including the Board of Regents, investigated the college. Ultimately, five faculty members were asked to resign. Despite the controversy, Brown’s administration helped the Oshkosh Teachers College recover after the fire and grow as an institution.

Photos

|

President Harry A. Brown |